Ancient Skulls Show Human Evolution Is More Like a River than a Tree

Genetic research has already established there are traces of Neanderthal (or Neandertal) DNA in the genome of modern humans. That’s not surprising. We’re all descendants from the first humans, so there’s a little Neanderthal in all of us.

Now researchers from North Carolina State University and Duke University have offered new insights into our past by studying the facial structure of prehistoric skulls. Their study, published in the open-access journal Biology, supports the hypothesis that much of the interbreeding between Neanderthals and our prehistoric ancestors took place in the Near East, which extends from North Africa to Iraq.

“Ancient DNA caused a revolution in how we think about human evolution,” said the study’s coauthor Steven Churchill, a professor of evolutionary biology at Duke University. “We often think of evolution as branches on a tree, and researchers have spent a lot of time trying to trace back the path that led to us, Homo sapiens. But we’re now beginning to understand that evolution is not a tree—it is more like a series of streams that converge and diverge at multiple points.”

For the study, researchers collected craniofacial data from earlier studies of human skull measurements. That resulted in a data set including 13 Neanderthals, 233 prehistoric Homo sapiens and 83 modern humans.

Craniofacial is a medical term that relates to the bones of the skull and face. You can think of the skull and face as a kind of billboard containing information about sex, health, ancestry, genes and the environment. Scientists have found they can learn a lot about a person by measuring various points on the face and skull.

“By evaluating facial morphology, we can trace how populations moved and interacted over time,” said Ann Ross, Ph.D., professor of biological sciences at NC State, in a press release from NC State. Ross also worked on the study. “Our work here gives us a deeper understanding of where those streams came together. . . . And the evidence shows us that the Near East was an important crossroads, both geographically and in the context of human evolution.”

The researchers focused on standard craniofacial measurements, which are reproducible, and used those measurements to assess the size and shape of key facial structures. This allowed for an in-depth analysis to determine whether a given human population was likely to have interbred with Neanderthal populations and the extent of that interbreeding.

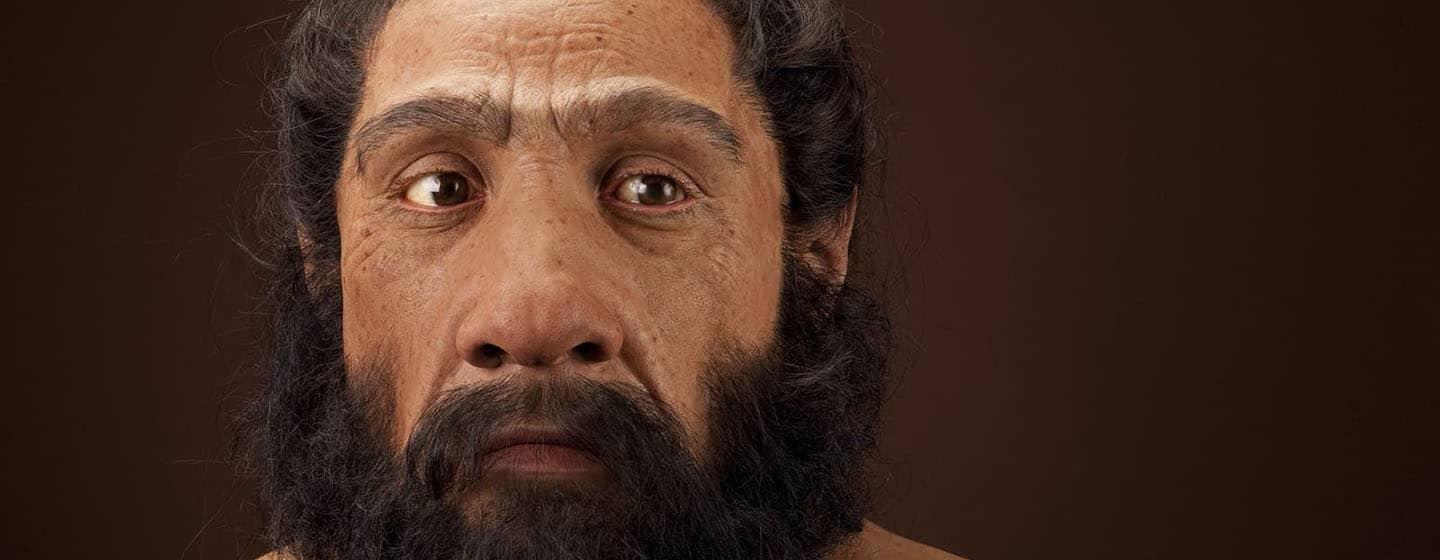

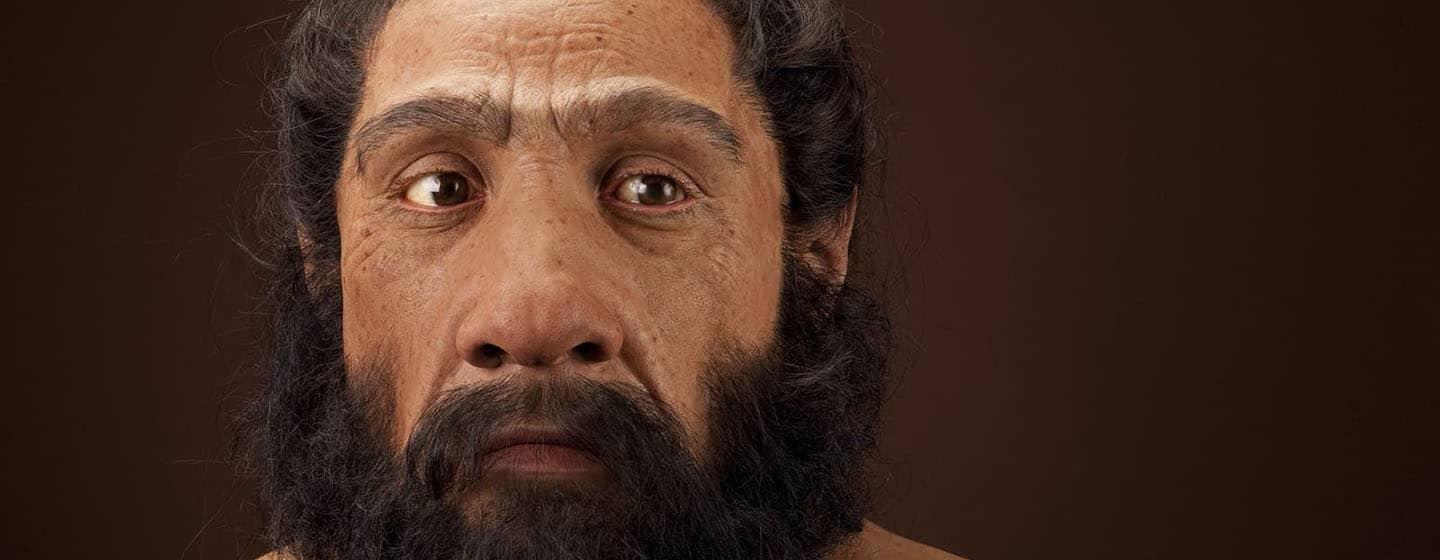

“Neandertals had big faces, but size alone doesn’t establish any genetic link between human populations and Neandertal populations,” said Churchill. “We conducted a robust analysis of facial structures and accounted for any environmental variables that could be associated with changes in human facial characteristics.”

The study was exploratory, had a small sample size and utilized craniofacial data in a new way. But …

“We also found that facial shape was a more useful variable for tracking the influence of Neandertal interbreeding in human populations over time,” said Ross. “Neandertals were just bigger than humans. Over time, the size of human faces became smaller, generations after they had bred with Neandertals. But the actual shape of some facial features retained evidence of interbreeding with Neandertals.”

“The picture is really complicated. We know there was interbreeding. Modern Asian populations seem to have more Neandertal DNA than modern European populations, which is weird, because Neandertals lived in what is now Europe,” explained Churchill. “That has suggested that Neandertals interbred with what are now modern humans as our prehistoric ancestors left Africa, but before spreading to Asia.”

Researchers say the results of the study are compelling. They now want to incorporate measurements from more human populations. Churchill says one focus could be the Natufians, who lived more than 11,000 years ago in what is now Israel, Jordan and Syria.