New Book Claims to Solve Mystery of the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke

Let’s go back to the North Carolina coast more than 400 years ago.

It's 1587 and 115 English settlers have arrived on Roanoke Island to start a new life. They are not the first English explorers. There had been three earlier expeditions to the New World, but this was the first to bring English women and children to America.

The goal of these expeditions for Queen Elizabeth I and explorer Sir Walter Raleigh, was to create an English capital in the New World.

The newest group to arrive included Governor John White’s pregnant daughter, Eleanor White Dare. In fact, several weeks after the colonists landed on the coast, Eleanor gave birth to the first English baby born in the New World. She was named Virginia Dare.

Soon afterwards, Governor White returned to England to get more supplies. His return was delayed for three years because of a war between England and Spain.

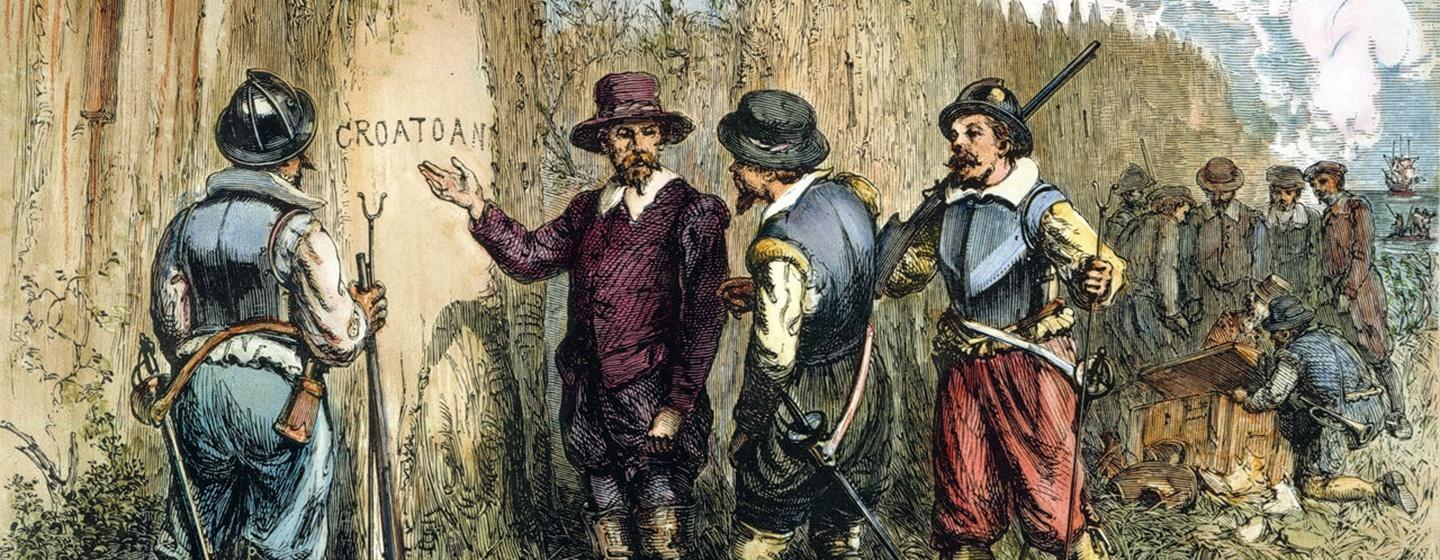

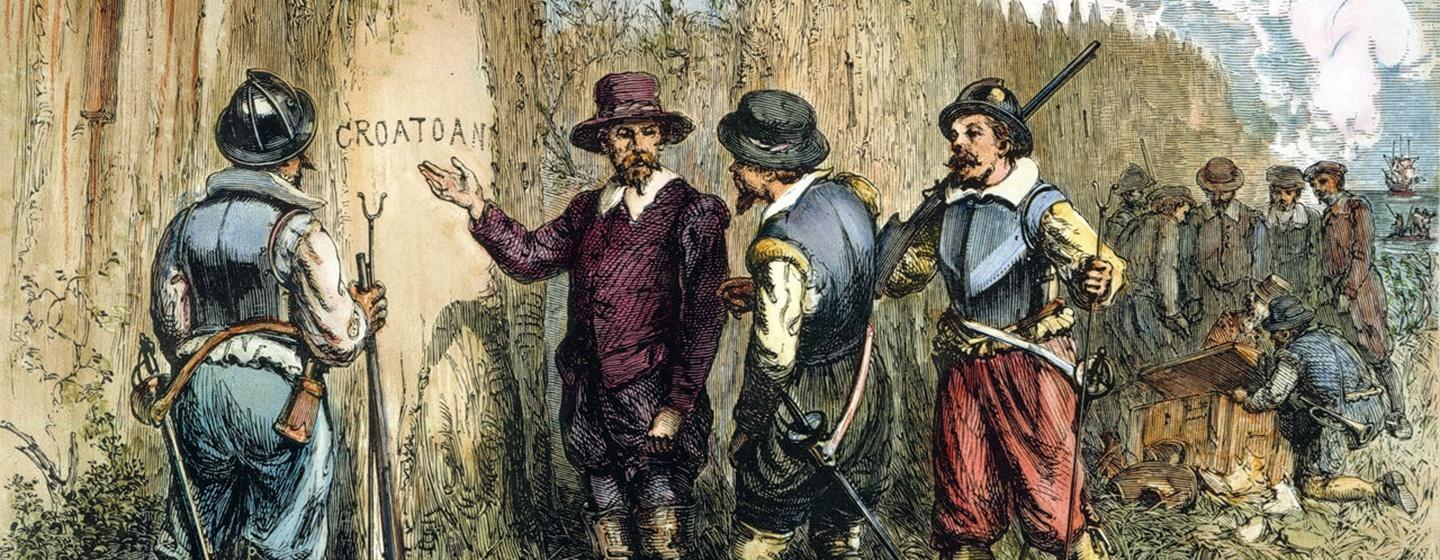

When he was finally able to make it back in 1590, on his granddaughter's third birthday, he found the colony deserted. The word 'CROATOAN' was discovered carved into a wooden post.

There has been plenty of speculation about the settlers’ fate in the centuries that have passed: death from disease, massacre by native peoples, orassimilation into a nearby native tribe, either as friends or slaves.

Multiple theories and a lack of conclusive evidence generated the mysterious moniker “The Lost Colony.”

But a new book by Scott Dawson maintains the English colonists who settled the so-called Lost Colony before disappearing from history were never really lost. They simply moved to live with their native friends — the Croatoans of Hatteras.

The book is titled The Lost Colony and Hatteras Island. It details the belief that Dawson has held for years, based on the research he has conducted and the artifacts he has uncovered: that the colonists lived with the native people in the 16th century.

“They were never lost,” Dawson told the Associated Press. “The mystery is over.”

Dawson and a team of archaeologists, historians, botanists, geologists and others have conducted digs on small plots in Buxton and Frisco, North Carolina, for 11 years.

Dawson and his wife, Maggie, formed the Croatoan Archaeological Society when the digs began. Mark Horton, a professor and archaeologist from England’s University of Bristol leads the project. Henry Wright, professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan, is the project’s expert on native history.

Researchers have found thousands of artifacts showing a mix of English and native life roughly four-to-six feet deep in the soil. Parts of swords, rings, writing slates, gun parts and glass are in the same layer of soil as indigenous pottery and arrowheads.

Some of those discoveries are on display at the Hatteras library. The rest are in storage.

In addition to the archaeology, Dawson cites written records. John White reflected on finding the writing on the post, “I greatly joyed that I had found a certain token of their being at Croatoan where Manteo was born ....” Manteo was a tribe member who travelled with earlier expeditions and was baptized a Christian on Roanoke Island.

A bad storm and a near mutiny kept White from ever reaching Hatteras. He returned to England without ever seeing his colony again.

Dawson also points to documents from the English colony of Jamestown that show the Roanoke colony did leave their camp to live with their native friends. And more than a century later, English explorer John Lawson found natives with blue eyes who recounted they had ancestors who could “speak out of a book,” Lawson wrote.

Dawson maintains the evidence shows the colony left Roanoke Island with the Croatoans to settle on Hatteras Island. They thrived, ate well, had mixed families and endured for generations.

In addition to the artifacts, the team found round post holes where natives constructed their homes that sat just 25 to 60 feet away from square post holes made by English during the same period.

“They were in the Indian village surrounded by long houses,” Dawson said.

“It’s not unlikely that one group might have gone up the Chesapeake, up the Albemarle,” adds Horton. “But I’m pretty confident one group at least, probably the pretty substantial part, came out to Hatteras Island.”

And to Dawson, that is the most important finding.

“You’re robbing an entire nation of people of their history by pretending Croatoan is a mystery on a tree,” said Dawson. “These were a people that mattered a lot.”