Reconnecting to the River

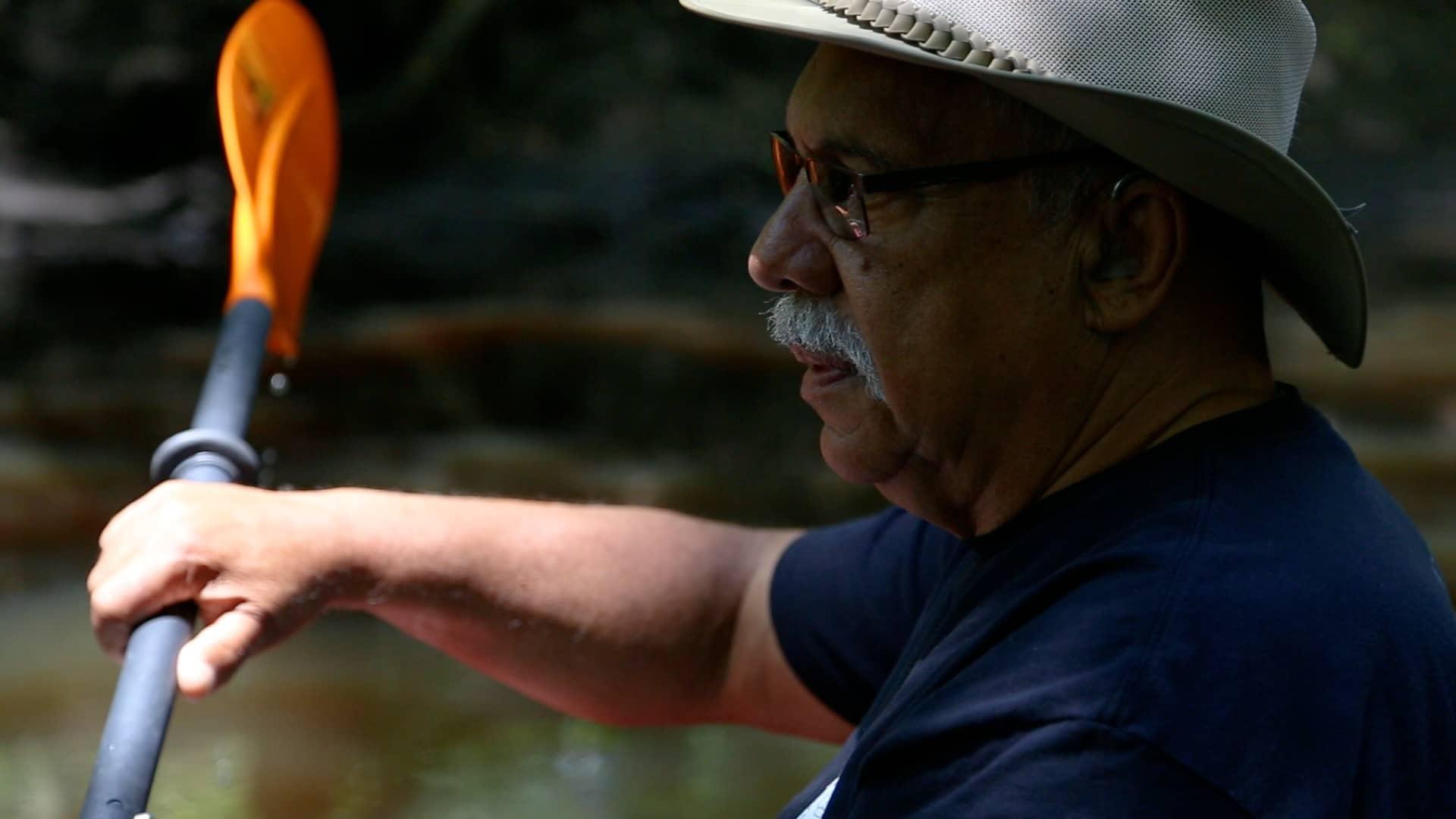

Kullen Bell raises his cupped hands to his mouth, and the sound of a mourning dove floats out over the Great Coharie River.

“That wasn’t there yesterday, that sweet gum,” he remarks, pointing out a slender tree lying across the river from the bank as we float on the current in a kayak and canoe. “One unique thing about our water, or our river: ... there’s a lot of twists and turns and bends, so it’s something new at every turn.”

The Great Coharie River (identified as the Great Coharie Creek on Google Maps) flows through the sandy ground of Sampson County, North Carolina. It’s the ancestral home of the Coharie Tribe.

The river is a blackwater stream, with dark, tea-colored water flanked by bald cypress and other wetland trees. The soft, sandy ground allows the river to cut a myriad of channels that snake and flow around each other in a braided pattern.

“Coharie and Lumbee and many other Indigenous peoples, in the southeast especially, share names with rivers. That is how our people identify,” shares Ryan Emanuel, a hydrologist at Duke University and a citizen of the Lumbee Tribe. “Here in the southeast, rivers are essential to Indigenous culture and history, and they always have been.”

Between 1729 and 1746, intertribal and colonial hostilities caused the Coharie to move inland, where they found refuge in the area around the Great Coharie River. This marshy land was seen as undesirable by settlers since it wasn’t productive farmland.

“They were largely outside the jurisdiction of colonial authorities,” Ryan explains. “All across the southeast, you find communities of Indigenous people who have survived as distinct cultures and maintained their identities in these types of landscapes.”

Coharie Tribal Administrator Greg Jacobs says when he’s on the Great Coharie River, he can tap into the emotions of his ancestors.

“Being creative in my mind when I go down the river, I can imagine my ancestors looking for a place of belonging, a place that was safe [where] they could raise their families,” he says. “I can feel fear ... I can feel people doing whatever they got to do to survive. But the beautiful thing is that I can feel the satisfaction of when they came to the Coharie River. ‘This is the place. My kids, they’re safe here. ... Here is where we stop running.’”

“So here it is, 2025, and we’re still on the banks of the Coharie River,” he continues. “It bears our name, and we love it and we’re going to take care of it.”

When Greg and his friend Phillip Bell, the Coharie River director, were younger, they often sought refuge in the river since they weren’t welcomed in the segregated town of Clinton.

“The river always was, [to] me and a lot of my friends, home or our recreation department,” Phillip explained. “We couldn’t go to town. We couldn’t go to the pools in Clinton because they were off-limits to minorities, so we could always go swimming here in the Coharie River.”

Greg also remembers the river being a resource to the community during that time.

“As a teenager, I came up during segregation,” he recalls. “Being a Native American, a lot of public recreational facilities weren’t available to me. But we had a beautiful place to go that we were treated equal and that we were safe, and that was the Coharie River.”

In addition to “community days” when neighbors would get together to picnic, fish and swim, Greg remembers exploring the river with Phillip during their childhood. “We would walk the banks of the river, fish. It would get hot, and we’d take our clothes off; we’d take a dip and put our clothes back on and go fishing again. So, it was a magical place.”

“Life was good then,” Phillip recalls. “But you know, things change, and so did the river.”

The river started to change in the 1990s after the area was hit by back-to-back hurricanes. The storms brought down trees that fell across and into the river, changing its shape and making it difficult to navigate. A beaver population initially brought into the area in the 1930s as an alternative income for farmers was left largely unchecked as the fur industry became less profitable. Beaver dams along the Great Coharie River backed water up onto nearby lands, sometimes impacting agricultural fields along the river.

Phillip recalls trying to get back to a fishing hole he used to visit frequently, named Daniel Hole after his dad, when he retired and returned to Clinton in 2012. He was surprised by how much the river had changed. “I had to wade through water and never did get exactly where I wanted to go because it was just too much water,” he said. “It was backed up all the way out to where our trucks used to park.”

“The problem was, the time that I was in school until I returned back home, the river had been purchased by the state through a conservation easement, and the land was leased out to hunters, and so there was no access for our people to go to the river and fish or to even access the river,” he explained. “That’s the thing that I couldn’t understand after having a life of growing up with freedom to go into the river to do what we wanted to do.”

Around 2011, Greg returned to the area for his first stint as tribal administrator. While he was talking with elders of the community, one of the women, Allion "Sis" Goodman, asked him what they were going to do about “our river.”

“She didn’t say what about the river, she said what about our river,” he recalls.

Greg remembers how she continued to talk with his sister about their childhood experience of the river and the memories connected with how the river used to be. He says, “sort of a spiritual thing took place in my mind.”

That’s when he went to talk to Phillip, nicknamed “The Great Coharie River Legend” because of his connection to the river, and remembers the conversation striking an emotional chord with Phillip as well. Greg remembers Phillip saying, “Have you seen the river? It’s become a swamp.”

“We decided that day we would take volunteers, and we would start doing what we could to clean that river out,” Greg said.

Phillip worked with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality to get permission to access the river and clean it out, and that began the Great Coharie River Initiative in 2015. He remembers rallying the tribe’s current drum team, a group of young men, to help him start clearing out the river.

“We just asked them, ‘Look, can y’all come help us Saturday clean out a section of the river?’ And I said, ‘It’s going to be dirty and nasty, but we’ll have a good time,’” he recalls. “‘We can feed you, but that’s all we could offer you.’”

Phillip says the first three or four Saturdays that they worked, they cleaned out probably a mile of river. “Fast forward,” Greg says. “Almost 100 miles of rivers have been cleaned out in Sampson County.”

Without context, it might seem like clearing trees and obstructions that naturally fell into the river is interfering with nature. But Ryan says that disregards Indigenous communities’ long history of interacting with natural systems and stewarding the land.

“The idea of pristine wilderness is a myth that [modern humans] created,” explains Ryan. “Here in North America for thousands of years, people have stewarded lands by taking an active role in managing them, whether that’s through fire or whether that’s through maintaining river channels. All of these things are integral to what Indigenous peoples consider to be healthy ecosystems.”

The buildup of debris in the Great Coharie River had created issues with water quality and flooding of nearby land, including agricultural land, which impacted people’s livelihoods.

An initial goal of the Great Coharie River Initiative was to clear a path through the river channels so that people could once again paddle the blackwater stream.

“From the perspective of Coharie people, a healthy river is one that has constant interaction with people through paddling, through fishing, through swimming and just being close to the river,” Ryan shared. “Because the river was closed off to them for so many years, it had devolved into an unhealthy state.”

Multigenerational knowledge of the Great Coharie River and what helps it function is held within members of the Coharie Tribe. Since the initiative has gained traction, this knowledge has been put in front of more and more organizations and, in the words of Phillip and Greg, gained the tribe more visibility and “seats at the table.”

“If you look at where we are now or the visibility of the Coharie Tribe today compared to back in 2014 or 2015, there’s no comparison,” Phillip shared.

“Indigenous peoples are observers of their environment, and they have been since time immemorial,” Ryan said. “They are scientists, technicians, philosophers, and they carry this deep knowledge. It’s not always recognized in the ways that we recognize it in academic spaces, but that doesn’t make it any less valuable. In some cases, it’s not only valuable, it’s essential for understanding and addressing the challenges that we face in society.”

Ryan says that ignoring Indigenous knowledge, especially when it comes to environmental issues, would be “a tragedy.” The Great Coharie River Initiative is proof of that.

“So many of the case studies and issues that we talk about related to Indigenous peoples and the 21st-century environment deal with ways that Indigenous peoples are left out of the conversation,” Ryan explains. “The story of the Great Coharie River Initiative is important because it shows how Indigenous peoples can not only take the stewardship of the environment into their own hands, but when they do, amazing things can happen.”

Phillip remembers witnessing a change firsthand as they continued to work on cleaning out the river. Of the eight young men that they had initially recruited, only one of them had a full-time job. When the same group returned the next year, all but one had a job.

“When that happened,” he shares, “it made it all worthwhile.”

“I’m not so sure that we’ve helped that river as much as it has helped us,” Greg said. “I think it’s helped us open our eyes to a greater purpose, a greater vision.”

“The greatest change that I’ve seen has been in our young folks,” said Phillip. “The drum team has gotten bigger. We have culture classes here now … We have younger folks that have grown up through this Great Coharie River Initiative era who are participants in those classes.”

“Kullen is one of our best examples that got away from home,” Greg shared. “Once he was introduced back into that, something spoke to him that changed him forever. Now, you can’t get him to stop … Something that was lying dormant inside of him, that river tapped into it and it sprang up.”

Kullen Bell, a relative of Phillip’s, is the watershed river coordinator for the Great Coharie River Initiative and leads groups of visitors in paddling trips on the river. He’s also active in other aspects of the Coharie Tribe, including the drumming group, Smokey River Singers. But he wasn’t always so active in his tribe or on the river.

“The first time I was introduced to the waterway was around 2015, 2016,” he recalls. “I was like, ‘This is insane, this natural resource in my backyard that I wasn’t able to enjoy as a kid.’”

He says getting more involved in leading Coharie River Tours brought him back home to his culture.

“I was living in Wilmington, North Carolina, and that’s a fast-paced life.” He said the river helped him “slow down and really, when I’m out here on the river, think about what’s important and what I want in life,” he shared. “Thinking of legacy and what you can do for your community.”

Greg and Phillip are in their 70s and are relieved that their work with the tribe and the river is prompting the next generation to carry the torch both in tribal culture and in stewarding the river.

“My mind has gone to, ‘What is going to be the long-range effect of what I do today?’” Greg said. “I’m proud of what I see in the generation that is here now. I’m proud of what I see as their wanting to be responsible. They’re wanting to take a seat at the table to make this world a better place.”

He talks about floating down the river with his granddaughter and hearing her express how she finds solace and comfort in the river. He’s reassured that a closer relationship with the river and nature has been restored in the community.

“So many more people participating, so many more people being responsible,” he says. “We know the importance, and that’s going to be passed down from generation to generation to generation.”

“The motivation for me for doing the river work is that I understand. I grew up in the river, and I understand this value,” Phillip shared. “I understand what it can offer someone who is troubled.”

“[The river] doesn’t have the same uses as it did to our ancestors, but it’s still important to keep it maintained, and I have tons of ideas,” Kullen said enthusiastically. “More of your 10-to-15-year plans on what this place could look like with proper care.”

Ryan says, looking to the future, “As a society, we have to do a better job of teaching about Indigenous peoples. And we have to do a better job of finding ways to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into our policies, into our management strategies and into the way we go about planning for the future,” he emphasized. “Whether that’s planning for climate change, planning for development, land use change, what have you. It’s essential that Indigenous peoples and their perspectives be part of this story.”

The Coharie Indian Tribe's restoration of their namesake river prompts a cultural awakening.

Learn how NC communities have increased their resilience to climate change by returning waterways to a natural state. Stories include how the Battleship North Carolina modified its marshy surroundings to adapt to rising sea levels, how Conserving Carolina is working to restore floodplains in western NC and how the Coharie Indian Tribe is reconnecting with the river they’ve lived on for centuries.

Off the coast of Wilmington, NC, the Battleship North Carolina team turns to innovative natural solutions to protect the ship from frequent flooding and rising sea levels.

Farmland is being lost to development at an alarming rate. What if solar energy could provide farms with steady revenue and share the field with valuable crops?

A farm in Biscoe, NC, generates renewable energy while its sheep keep the grass trimmed without gas-powered machinery, a win-win for climate change resilience.

Can farming and solar-energy production coexist? EnerWealth works with farmland owners and energy co-ops to make sure rural communities get a piece of the pie.

STREAM ANYTIME, ANYWHERE